Ship’s Log Week Thirty Six

Final Pacific Ocean Passage

On 5th July 2025, nearly five months and more than 6800 nautical miles after the start of her journey across the Pacific Ocean Walrus set sail from Musket Cove, Fiji, on, the penultimate leg of the first half of the 2025/26 World ARC Rally, her final passage starting and ending in the world’s biggest ocean (Walrus’ journey across the Pacific started on 8th February 2025 when she sailed under the Bridge of Americas, which marks the dividing point between the waters of the Panama Canal and the Pacific Ocean). Walrus’ destination, Vanuatu, an archipelago of eighty-three islands, that, after all the wonderful sights we had seen, incredible people we had met, was to provide us with yet more unexpected and thought-provoking experiences.

The Pacific Ocean covers one third of the earth’s surface, more than sixty-three million square miles, an area larger than all the dry land on earth. It contains more than twice the volume of seawater of the Atlantic Ocean and is twice the size. On average it is more than two and a half miles deep and at its’ deepest there are 6.8 miles of ocean beneath the surface - Davy Jones locker (which I can’t bear to think about) is a long way down. As Laurence Bergeron (Over the Edge of the World, 2017) reflected in his tale of Magellan’s 16th century travels across this vast expanse of water, the Pacific Ocean alone might determine reconsideration of the way we think about our planet - is it really planet earth? Or might Planet Ocean be a better fit? David Attenborough (whose voice I have often imagined in my ear during Walrus travels around the globe) called it the blue planet.

Sailing on Walrus across the Pacific Ocean for more than seventy-two days had given us an intimate, first-hand, day and night, breathing in, breathing out and just occasionally - but luckily rarely, under the water, feeling for the Pacific. I hasten to add for those who might be concerned for Walrus’ crew’s welfare - any under the Pacific moments have all been planned and primarily focused on checking the state of Walrus’ hull. We had experienced the deep, deep cobalt blue of the waves day after day, stretching as far as the eye could see in all directions, with ripples and white wave crests varying in intensity and frequency depending on the wind strength, rippling and sparkling with phosphorescence on moon-filled starry nights. In contrast, the daytime icy blue of the horizon-level sky, deepening to sky blue above, with rarely a cloud, unless to warn of approaching squalls, of which Walrus has had her share.

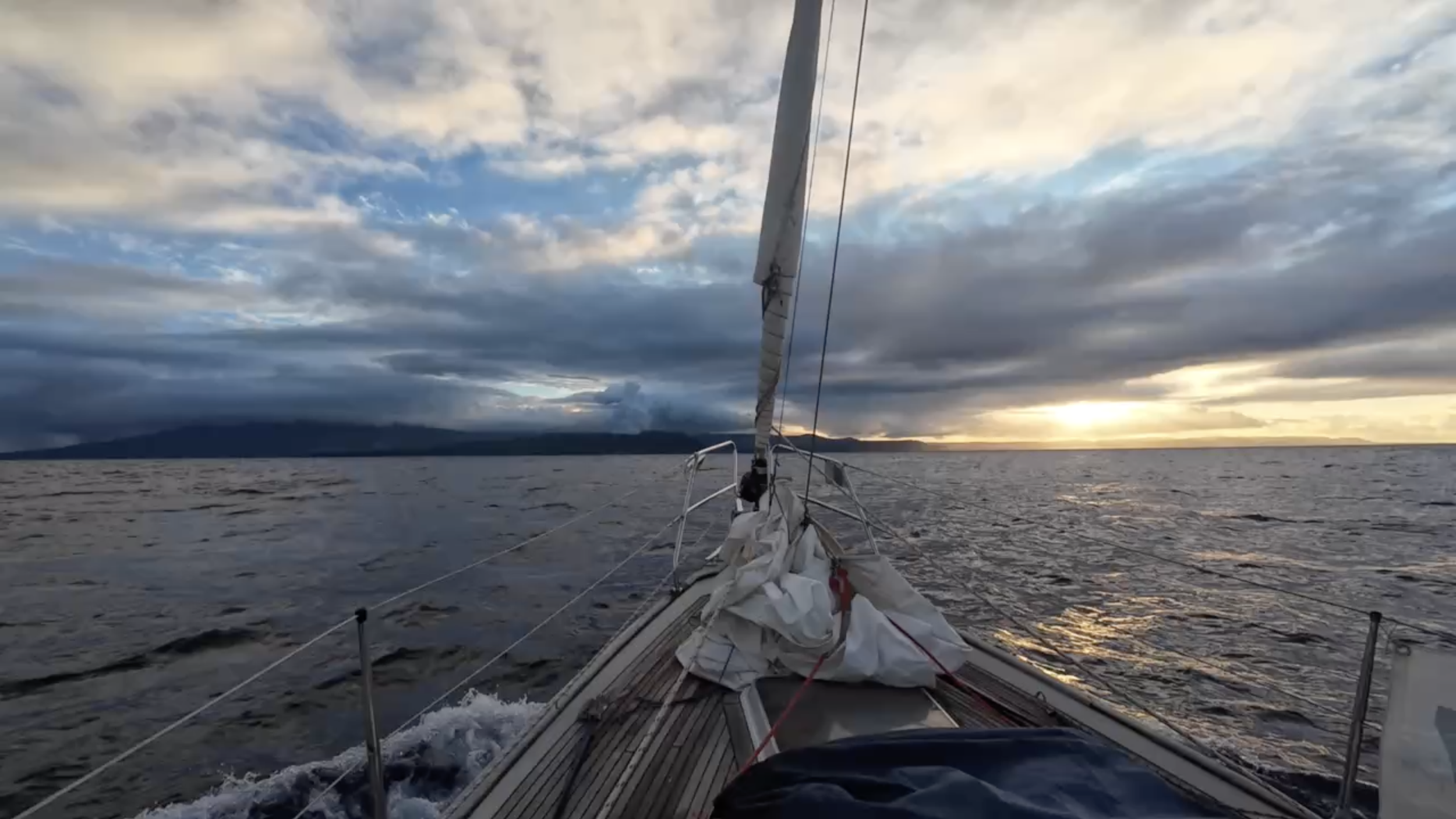

On board Walrus, once the passage was underway, time and motion turned topsy turvey with the constant round of watch changes - 2 hrs 30 mins on and 7 hrs 30 mins off rotating round the clock, with the added dimension of time zone changes every 15 degrees longitude. The Pacific Ocean has a swell, with rolling, undulating swathes of seawater, on this passage, coming from two directions, sometimes towering above Walrus from the port side, sometimes aft, looming above her stern, as she dipped down one trough, before rising to the top of another. Sometimes slapping hard against her hull as she righted herself and re-orientated her bow in the direction determined by the autopilot, while riding the counter swell.

As I looked out of Walrus’ cockpit on my first watch of this leg, I mused on the challenge of describing the unique experience of being at sea. Different from reading a super-quick, but in-depth, AI generated, facts and figures version, which I love and marvel at - who needs to learn anything when information is at hand at the drop of a hat… or the press of a button, perhaps even quicker? Friend, Diane, likened the experience of an ocean passage to being in freefall, a description I can relate to.

Although Walrus’ passage to Vanuatu was one of the shortest between stops, a mere three and a half final days at the mercy of, or to enjoy, the Pacific Ocean, depending on your perspective, it had no less an all-encompassing, completely-suspended-from-everyday-life, onslaught-on-the senses feel. Have you ever had a ride on the theme park ride that flattens those game enough to give it a try, against the wall of a circular drum, as the floor drops away? Skirts and scarves flattened against the sides, legs and arms akimbo, pinned in place by centrifugal force - when Walrus is heeled over gravity is difficult to defy and I sometimes feel like the thrill-seekers on that theme park ride. Walrus rocking and rolling in response to the Pacific Ocean swell put paid to balance and normal movement, with every journey from heads (bathroom) to galley, galley to cockpit up the well-trodden four steps, cockpit to foredeck and so on, an exercise in holding on and a careful execution of hand and foot positioning to avoid falling over, falling in or at least, crashing into and flattening another crew member. At times, I’ve found myself envious of the howler monkeys we had spotted in Panama, with their prehensile tails making movement between one swaying branch and another look easy.

On this passage Walrus’ sails were set in the straightforward sail plan of main and foresail, sometimes changed to poled out foresail alone when the wind direction changed to come aft, sometimes reefed when the wind strength increased. Gerald, as ever, was a whizz at making adjustments to ropes, thinking of new possibilities for maximising Walrus’ course and speed over ground, while at the same time creating the most remarkable of spreadsheets to aid planning and predict Walrus time of arrival.

In the main we had good winds, South Easterlies, sometimes Easterly, ranging from Beaufort Scale Force 4 (small waves becoming larger; fairly frequent white horses) to Force 6 (large waves begin to form; the white foam crests are more extensive everywhere, some spray). The Beaufort Scale was devised in 1805 by Francis Beaufort, a hydrographer in the Royal Navy. There’s a wonderful tale on the BBC Sounds Illuminated Series of how these empirical, almost poetic sounding, descriptions of the effect of the wind at sea and on land evolved. Thanks to friend, Jo, for the recommendation, I listened to the podcast one night while on watch wearing my life-jacket, sitting in the cockpit tucked behind the spray-hood, experiencing a Force 6 (described in Walrus logbook as a night with ‘rough’ sea state). On reflection, I’m not sure whether the crew member who wrote ‘rough’ in the logbook was referring to the sea state or the way they were feeling at the time. I am fortunate (touch wood - or knock on wood, if you’re American) in not having experienced seasickness no matter how rough the sea and no matter whether I’m above or below deck. I’ve learned that seasoned sailors and those new to the seas, alike can be prone on occasions to the unpleasant side effects of seasickness. On this passage both Dicky and Ted - the most experienced and seasoned of sailors, suffered a period of debilitating appetite-suppressing seasickness early on. Both fought through like troopers not missing a watch despite looking and feeling a little green around the gills, as the saying goes.

I generally spent night watches perched between two winches on the edge of Walrus central cockpit, where I could easily see the sails and check whether a little more or little less sheeting in or out might be needed. At the same time, this was a good spot to stargaze - the blue-black velvet South Pacific sky had the most amazing, mesmerising view of far away galaxies. Ted and I shared a preference for the same favoured watch-spot, Dicky tended to tuck into a corner of the cockpit, keeping an eye on the steering (Walrus autopilot had a tendency to click out of auto onto standby when you were least expecting it, causing a brief moment or two of havoc with the sails and direction of travel) or at the chart table keeping an eye on instruments and recording Walrus progress in her impressive logbook. Gerald, could be anywhere and usually was, on the deck making adjustments to sheets and halyards, or listening to an ‘In Our Time’ podcast. He was a self-confessed and devoted fan of Melvyn Bragg - is Melvyn Bragg the David Attenborough of the human world?

And so we settled into our routine for the voyage. Like ships in the night passing each other briefly between watches and over supper, which we ate around the cockpit table, usually from, named-by-Dicky, ‘dog bowls’, that had saved many a carefully prepared meal from landing on the floor. These red plastic bowls with handles, had been a fortuitous last minute purchase from Morrisons in Gibraltar, one of the few advantages of having spent a week trying to get Walrus’ spare parts through customs. Three and a half days after setting out, on a day when the seas had calmed, Walrus crossed the finish line for Leg 7, rounding the headland past high cliffs of red earth, topped with deep, dark trees creating a spiky silhouette against the early evening sky.

The full moon reflected on the water of the bay as we motored the final mile or so into the bay known as Port Resolution, named after Captain James Cook’s ship. Dicky positioned Walrus as close to shore as depth would allow and as far away from other yachts as necessary to avoid contact, before dropping her anchor. Proximity to Tanna Island’s shore was all important given the beleaguered, almost-at-the end-of-its’-life state of Walrus’ dinghy.

Landfall is a much anticipated joy after days at sea; being the smallest boat in the fleet Walrus was also the slowest through the water, and so it was that we arrived in Vanuatu just a little too late to clear customs. Delayed gratification was the inevitable consequence as we celebrated our near arrival, onboard overlooking the most gorgeous of hidden away anchorages imaginable. Keeping fingers crossed that things would workout paid off, or rather the diligence of Lesley and Paul, our ever resourceful World ARC support team, paid off. A visit by Vanuatu immigration and customs officers the following morning, had been arranged to clear Walrus’ crew into Vanuatu on Tanna Island. We were to meet with the officials in the Port Resolution Yacht Club at 11.00am.

Vanuatu - last stop before Australia

I confess to having thought little more of Vanuatu than recognising its geographical significance in relation to Walrus’ circumnavigation and the end of the first half of the World ARC Rally - translated as.. ‘phew…nearly there, last port of call, let’s get on with it… how much more exciting can it be after all the amazing experiences since sailing into the Pacific Ocean in February 2025?’ With hindsight, and in retrospect I have questioned myself and had a stiff self-talk, reminding myself to be attuned to every new place and opportunity, no matter how world-weary or eager to move on I might be feeling. Blasé is not an option… If I had any preconceptions about Vanuatu these were based on an unfounded hypothesis that this archipelago, being within the region of Oceania, alongside westernised Australia and New Zealand would have succumbed to the demands of the tourist industry, offering visitors a lifestyle-experience that they recognised, in exchange for dollars.The humbling human stories and genuine welcome that we received swiftly put paid to these thoughts.

Vanuatu was previously known by the names ‘Great Cyclades’ (Bougainville, 1768) and the ‘New Hebrides’ (Cook, 1774). It was at one time, unique, in being ruled simultaneously by the English and French, having both education and justice systems running alongside each other. The Vanuatu archipelago became independent in 1980, establishing a universal language, ‘Bislama’, for its mainly Melanese population. Over the course of nine days Walrus sailed from Tanna island in the south, with its active volcano, to Erromango, only accessible by yachts mooring in a small bay, and finally Port Vila, the capital on Efate Island, positioned in the middle of the archipelago. The experiences we had on our brief visit to each of these islands were unique and unforgettable. For Walrus, it was to be the last outing of her troubled dinghy and an ignominous parting of the ways.

Common to the three islands was a strong sense of community, a pride in Vanuatuan culture and customs, an assumption of reciprocal respect and an expectation that we, the visiting yachties, understood the nature of a subsistence economy and the role of ‘barter’ - the exchange of western goods, such as rope, cooking oil, clothes, pens and paper for local home grown fruit and vegetables. We were welcomed like long lost friends, due to the long-standing relationship that the World ARC had developed with the communities on Vanuatu over the period of the past two decades and also, perhaps down to an innate hospitality of the Vanuatuan people. From the get-go we experienced a sense of warmth and social connection, despite differences in life experience. It seemed the Vanuatuan’s tradition and identity, commitment to forebears and way of life had remained largely unchanged over the centuries; resistant to wider, worldwide influences. We learned that Vanuatu was a democracy with fifty-two elected politicians who sat in Parliament in Port Vila on the island of Efata. There stood a separate nearby building to host the council of Chiefs, representing the tribes of Vanuatu and responsible for holding parliament to account for maintaining the customs, culture and traditions of the islands. No law could be passed without the Council of Chiefs’ approval. Vanuatu remained firmly tribal in its structure. On Tanna Island there were six tribes, each tribe owned the land that their people lived on, or rather the chief of the tribe owned the land, which was passed down father to son.

Tribal life was tempered by a system of co-operation for the benefit of all, and resulting in shared provision of a school and other basic facilities for the families of all tribes. Was it the strong, shared sense of community and culture that had led to Vanuatan people being voted the happiest people in the world on three occasions, I wondered? I’m sure the verdant, abundant countryside, providing a safe, crime-free place for children to grow up, explore and play was a contributory factor and one that, in England, in the main, we have lost in the mists of time.

Tanna Island

On that first morning, Walrus’ crew had spotted, what we thought was the yacht club, perched high up above Port Resolution Bay in a clearing between the trees. So it was that on 9th July we eagerly clambered aboard Walrus’ rapidly disintegrating dinghy, a sorry sight, her transom held on with an intricate cat’s cradle of string and, despite this, water incoming at a rate of knots, to motor the short distance to shore. Gerald tied Walrus’ dinghy to a fallen tree amongst traditional wooden dugout canoe-like craft with two balancing branches on one side, and the WARC fleet’s raft of very-much-smarter-than-ours dinghies on the other and we set off on foot across the shore to find the dirt-track path that would lead us to Port Resolution Yacht Club, high above us on the land at the top of the red earth cliffs.

We huffed and puffed (it’s easy to get unfit whilst at sea) and clambered our way to the top. After a false start we found the woodland, or rather rainforest, track that led around a corner, up a steep hill to arrive at the Yacht Club. A small corrugated iron structure, with old two-seater sofa on one side, extended corrugated iron roof held up by roughly hewn posts, over a handsome trestle table on the other. Well-weathered flags from around the world, including the World ARC Rally flags from years gone by and our own 2025-26 rally hung from the roof of the structure.

There was a mown lawn, half a dozen shrubs and a few trees, sloping away from the club and down towards the edge of the cliffs, providing an arrestingly beautiful glimpse of the volcanic rocks tumbling down into the azure waters of Port Resolution cove, with it’s sea of World ARC masts, Walrus amongst them, waving gently to and fro. Three or more dogs and some young puppies gambolled around, as immigration officers created a makeshift office on the little table space available.

These were the circumstances when we checked in to Vanuatu, I shall forever hold this scene in mind when waiting in an airport’s seemingly unending queue (line) to get through customs. Werry, the commodore of the yacht club, sat on the old sofa, taking in the concentrated and sometimes intense activity of World ARC Fleet arrivals and departures, with a patience and unassuming manner that belied his years of wisdom and dedication to overseeing the maintenance of this beleaguered but symbolic outpost. I sat down on a green plastic garden chair nearby and asked Werry for his thoughts about life on the island. We talked about the cyclone that had hit Tanna Island the previous December, how it had destroyed the yacht club premises and simultaneously flattened the woven straw houses that were home to villagers. He talked about how tribes people worked together to rebuild their community. Previously houses had been made from circular woven mats of dried palm branches. It was Werry’s view that the circular nature of these structures made them more resistant to the winds’ devastating forces, nevertheless their strength had been insufficient in the face of, what had evidently been an unprecedented cyclone season. Werry expressed a scepticism about the decision to rebuild these straw houses in a rectangular or square shape with flat woven walls that he believed would tumble like a house of cards if the next cyclone season was as bad as the last. His narrative spoke of a certain resignation in the face of nature’s adversity, as he described the destruction caused by the cyclone and acknowledged that it had been ‘scarey’, my words not his.

Our conversation drifted to the traditional ways of the island; ways that from a western, first world perspective might seem primitive but that, over the course of the few days that we spent in Vanuatu I was to re-evaluate. Werry explained that the tribal dances we saw during our visit were a way of marking stages of children’s development, that the rite of passage and initiation into the adult tribal community was revered and celebrated. Songs and dances were a legacy passed down from generation to generation, binding together children, parents and grandparents into the weft and warp of the island’s social network. They were shared with visitors, as a way of introducing others to the Vanuatuan’s way of life, and as such, the intention was not just entertainment but rather a welcoming ritual binding islanders and visitors together for a moment in time. Boys aged between 6 - 10 yrs spent a month away from the tribe, being taught the skills for adult male life - how to fish using spears, cut down trees to provide material for building, kill pigs for roasting and in days gone by, fight, kill and devour the members of competing enemy tribes. The month’s initiation culminated in boys’ circumcision, feasting, singing and dancing whilst wearing the traditional grass skirt costume. For girls, a similar celebratory dance was performed by the women of the tribe to mark the event of their first menstruation.

Later that afternoon, after a forty-five minute four-wheel pick-up truck ride along dirt tracks cut deep into the side of the rainforest we gingerly unfurled limbs and released our grip of the sides of the truck, having held on for dear life as, at pace, the vehicle dipped and climbed, twisted and turned across steep hillsides. We had arrived in Kastom Village, home to a tribal community living amongst the trees on a small plateau overlooking Yasur volcano.

As the events of the afternoon and evening unfolded I found myself thinking back to a classroom in the first year of secondary school, more than half a century ago), wishing I’d paid more attention to the Yr 7 geography teacher at Whyteleafe Girls Grammar School as she valiantly tried to teach girls who were more interested in gossip, pretty much anything other than the lesson, and definitely… boys, about communities and cultures, the shifting of tectonic plates, hotspots on the earth’s crust, and the formation of volcanos. Most of what I had learned about other countries had come from National Geographic magazine articles read while waiting for the dentist or in the loo of friends’ parents’ houses. Something I now regret and am making up for on Walrus’ epic journey around the world.

As we took in the peaceful surroundings and stunning view, the tribes’ womenfolk and girls greeted us, placing garlands made from twigs, flowers and leaves around our necks. Gradually the women were joined by men in grass skirts emerging from a village of woven straw houses camouflaged by the rainforest. As the World ARC crew members took their places seated on rough benches made from bamboo poles lashed together, I pinched myself and made a vow to remember every second of this unique experience. Not sure what to expect next, we waited while the villagers gathered. In front of us, a flat, area of bare earth, a natural stage with jaw-dropping backdrop, Yasur’s smoking volcano. Even the most elaborate of stage productions could not match, the raw authenticity of this performance. First the women and girls, variably carrying small woven sacks, beaten rhythmically to produce an earthy, percussion accompaniment, then the men and boys dressed in dried grass skirts and some with sticks to emphasise their warrior status, performed the traditional dances that Werry had described as being those that mark the events of the passing of time and the rites of passage of tribes people. Young girls and boys were being inducted into the ways of their elders, it was heart-warming to watch as children mirrored the adults with enthusiasm, determined to play their part. There followed a demonstration of how to create fire by rubbing a stick against wood, with some dried moss-like plant creating the fuel. Then an invitation to try our hand, proving that years of matches and lighters had dulled our synchrony with natural materials. Finally, we were offered a lump of something sticky, which, at a guess, I’d say was plantain cooked-in-coconut-milk, wrapped in banana leaf. World ARC Team leader, Lesley, surreptitiously passed me her gift of food, to disguise her distaste and avoid offending our hosts.

As we said our goodbyes and clambered back into the pick-up trucks, I watched the communal activity, involving young and old alike. I recalled the school lunch time scenes we had seen earlier in the day when children confidently greeted us as they walked along a track between home and school, played in groups under the trees around the edge of the playing field or wandered with the chickens and pigs between the village buildings. A consequence of spending days at sea is the opportunity it has provided to read books that have been on a list of ‘must dos, one day’. One such, Dr Benji Waterhouse’s ‘You don’t have to be mad to work here?, a psychiatrist’s first hand account has prompted many a moment of reflection about the state of things, not in a ‘Those were the days’ kind of a way… More of a ‘How did we get in this pickle? Have we got something wrong?’ Kind of a way. Was this the answer to happiness? The subsistence economy, that I had previously described as primitive. The strong values of this Vanuatuan social structure, seemed to provide children with a childhood uncluttered with the trappings of consumerism, a recognised place in a strong inter-generational community and opportunities to explore their world through play in an environment that was abundant with nature and without the urban and suburban clustering of humanity. Am I at risk of looking through rose-tinted spectacles on a whistle-stop visit? I guess there’s a halfway truth and that sense of social connectivity and the ritual and shared rhythm of daily life in these tribal communities provided a secure, predictable environment in which children could thrive. But, Vanuatuan tribes were not 100% self-sufficient, there was a reliance on western charitable funding when things went wrong, in particular when the force of climatic catastrophe had torn the islanders’ fragile and limited infrastructure apart. And with that a vulnerability that lack of autonomy brings.

Onwards and Upwards

Walrus crew was by now back in the truck, with Pauline, Lee and their daughter, Sarah from yacht, Samsara, racing past Avatar-like scenery (Sarah’s description - remember the film?) as dusk approached. Sarah, now twenty had visited previously as a child when her parents had sailed with the World ARC a decade ago. Somehow I found Pauline and Lee’s pragmatic approach to revisiting this sometimes challenging, often demanding voyage reassuring. Yasur Volcano, they told us, had been one of the major highlights on their first circumnavigation. Could it live up to expectations, I wondered, or would it disappoint?

Volcanos had formed the basis of so many of the islands we had visited but none were as dramatic as Yasur. The truck pulled up alongside others a few hundred metres below the rim of the volcano. As the dark of the night enveloped us, we clambered up a roughly marked pathway worn down by passing feet, on our way to view this very much live, and potentially dangerous volcano, up close. A strong smell of sulphur hung in the air around us, the path crunched underfoot as we made our way over the brittle lava rocks and pebbles, the residue of past eruptions. The rim of the volcano was marked by a flimsy looking wooden barrier (no ‘health & safety’ regulations here), which we gravitated towards and gathered around, initially seeing nothing other than a dark chasm in the ground ahead, dauntingly close.

Once we’d reached the summit there was, what seemed like an interminable wait, probably only ten or fifteen minutes, before a deep, earthy rumbling, rising to a roar filled the air. Holding tentatively to the wooden rail and peering down into the depths of Yasur’s volcano, an area of molten rock turned from yellow to fiery red orange as the roar of volcanic activity grew and then faded. Some minutes later, and further around the rim of the volcano, closer still to the source of the molten lava, the rumble then roar reverberated again, a sound that I could feel in the pit of my stomach. With fearsome force a burst of fiery lava spewed up hundreds of feet into the air from the void beneath our feet. A palpable awe and excitement rippled through onlookers. Over the next half hour, we watched mesmerised by the force of nature as the roaring and spewing of lava below us electrified the night sky. All too soon it was time to head to the truck for the ride back to dinghies resting on the shore and Walrus in the bay. The end of a never to be forgotten day on a remarkable island that still had more to give.

A World ARC Tradition - Exchange of gifts and farewell to Tanna Island

Back at Port Resolution Yacht Club the following day there was an air of eager anticipation and a hive of activity in preparation for what had evidently become a much anticipated annual ritual between the World ARC fleet and the tribes people of Tanna Island, the event, an exchange of gifts. The families of the World ARC fleet spent the morning on the seashore preparing songs for a performance. At the appointed time Walrus crew along with WARC fleet members, totalling nearly a hundred people in total, clambered up the steep dirt path to the yacht club. The villagers had lined the path with branches bent over to form an arch in honour of the celebrations. As we entered the Yacht Club grounds every one of us was given a beautifully crafted, hat woven from palm fronds and decorated with fresh flowers, each a work of art in itself. We took our places seated on the ground or standing, opposite school children, sitting cross legged, waiting, with patient expectation. As with all good celebratory events, there were speeches, first from Werry, thanking the World ARC fleet for visiting and inviting us to enjoy and join in a performance by the Tanna Island School children, followed by Lesley, representing the World ARC fleet, in turn, thanking the islanders for their hospitality and explaining that, after performances the fleet would conclude with the gifting of items of food, clothing and other essentials.

The mingling of cultural traditions and shared experience transcended the differences in language and geography. The women of the village who’d spent hours making the gorgeous woven hats we were now wearing sat to one side of the school children avidly watching the performances. The men dotted in groups behind them. One woman was so taken with the singing that she got up and danced in a flurry of swirling skirts to the audience’s delight. When the performance ended and all that remained of the area that had once been the stage, was a towering pile of bags with gifts from World ARC fleet members, the villagers set about dividing items into six, so that each of the tribes benefitted equally. Children and adults mingled. Bob (from Salinity) had two young children absolutely entranced with a game of ball and his demonstration of hand puppet shapes.

An exchange with an elderly lady, who I took to be one of the grandparents of the school children, established a connection, when she learned my name, she beamed took my hand and told me that her grandfather had called her by the name of, ‘Alison’ too. In broken English, she haltingly told me that she loved it when the World ARC visited, we were, apparently the only visitors who held a proper celebratory event. We enjoyed the moment and squeezed hands some more, before saying goodbye. Lunch was a buffet set out on the trestle table that had only recently been used to complete the official bureaucracy of immigration check in and check out. Afterwards, when the excitement had died down, the school children headed home for an early end to the school day and Werry and other yacht club members had taken a seat, we drifted back to our boats and prepared for the onward journey.

Erromango Island - Cannibal Soup

Walrus crew, although a little reluctant to move on so soon, set off for the island of Erromango late that evening, with the aim of a day time arrival. Our reward; a gentle sail overnight with an Easterly 10-12 knots on the beam. The gentle slurp, gurgle and whoosh of the waves against Walrus’ hull as the sky lightened over the dawn watch, and we whistled through the water at a speed of 5-6 knots, a wonderful reminder of the joy of sailing. Walrus arrived in a wide bay bound by cliffs and a yacht club of similar status and state of repair to that of Port Resolution. Below it, a scattering of half a dozen village houses alongside a sweep of pebbly beach. The beach extended either side of the mouth of a river and to Walrus port side the valley rose up, with a covering of trees and tumbling rock.

Dicky navigated to a suitable anchorage and once stationary we stopped for a cup of tea before deciding what to do next. There was the usual post-anchoring speculation over whether the anchor would hold, whether the depth and the amount of chain played out was sufficient. These were perpetual considerations, with various views forthcoming from crew members. Ted, with his extensive experience of anchoring off the beautiful Suffolk coastline favoured reversing to bed in the anchor, Dicky’s preference was to get a decent length of chain out as soon as possible (a length that was three times the depth of the water seemed to be the metric to aim for). Gerald had previously favoured attaching an anchor marker, that he had painstakingly mended, to the chain to mark the anchor position. I guess we’d become a little more anxious about anchoring since our brush with a coral bommie off Malolo Island.

Suffice to say a happy compromise was struck, and all was well over the course of the two nights we anchored in Dillon’s Bay, or William’s Bay, as it was also known locally. Named, we learned later, after the last missionary to be killed and eaten by the, then cannibalistic tribes living on Erromango. Fortunately times had changed… or had they?

As we started to consider how we might get ashore, given Walrus dinghy’s poor state of repair and the not insignificant distance to the only place that looked suitable for landing and securing a dinghy, a dugout canoe with the single figure of a man skulling determinedly towards us came into view. David, introduced himself as commodore of the yacht club, he held on to Walrus stern as we lowered the swim ladder and invited him on board. David proffered a beautifully woven basket filled with local vegetables and fruit, and in return asked for cooking oil and rope, which despite Walrus’ paucity of storage space, we were able to provide. Once this initial important business transaction had been satisfactorily concluded, David accepted the offer of a cup of coffee. Gerald, ever active and seeking new adventures, asked permission to have a go in David’s traditional wooden dugout canoe (or pirogue as they were known in French Polynesia). A moment or two passed before David responded, indicating, in an act of great trust given the importance of a canoe for transport and fishing, his agreement. Before you could say, ‘Jack Robinson’ Gerald had lowered himself into the narrow canoe, not without some difficulty; the space was designed for someone with shorter legs. He set off, gingerly at first, but before long, once he’d mastered the art of the single wooden paddle, distancing himself from Walrus. Meanwhile, we learned the canoe had been hand carved specifically for David (a wiry man of somewhat indeterminate age - could be fifty years old or maybe sixty pushing seventy) by a relative, whose canoe-crafting skills were known to be the best on the island. No wonder he’d been a little reticent to give his consent to Gerald’s request. Gerald skulled just far enough for David and the remainder of Walrus’ crew to wonder whether he’d jumped ship for a new life on Vanuatuan shores, before turning and returning the canoe to its owner.

Over the course of that day other World ARC boats anchored alongside Walrus and Imi Ola, the early arrivers. The World ARC community spirit and generosity prevailed. Peter and Deborah, on non-sailing yacht, Entre Nous, kindly invited us on board that evening for cocktails and snacks. We enjoyed the rest of the fleet’s colourful dinghy party with dry feet and marvelled at the comfort of the wide aft deck of a catamaran. The dinghy party attracted some twelve dinghies, which rafted together made for a colourful sight. The arrival of Nakula’s Japanese crew dressed as pirates and waving a skull and cross bones added the icing on the cake. Nakula had earned a reputation as the karaoke party boat and their crew were cheered wherever they went. Deborah, helmed by able crewman, Kurt, arrived the next morning to take us ashore. Big sigh of relief on my part… no need to weather the not insignificant distance to shore in a barely floating dinghy.

Our day on Erromango was memorable for the guided tour of the valley given by David, the marvellous spread of a buffet lunch, including freshly caught lobster, with surprise entertainment provided by a makeshift skiffle band and a tour of the tribal burial caves given by the chief of the tribe. David led us along the main village dirt track, past simple tin shack and wooden houses. A group of Seventh Day Adventists were sitting on the ground by the path in an enclosed area, engaged in an act of worship. It seemed the missionaries had left Erromango with a number of faiths to follow, with associated rituals maintained alongside tribal traditions. He showed us inside the cool communal shelter that the tribes people had built from large wooden beams and woven palm fronds and explained that villagers gathered together in the building when a cyclone threatened the destruction of their homes. I wondered whether climate change was to blame or whether cyclones had always been as significant and life-threatening.

We left the village behind as we walked across the school playing field nestled in a verdant valley that reminded me, in some ways, of my children’s rural Kent village primary school - except for the large Banyan tree in the far corner, in place of an oak tree. David led us single file through lush vegetation, past tethered goats to an area, which to the untrained eye appeared to be wild woodland. To David and his family, it was a source of medicinal supplies, a piece of bark from one tree was torn off and passed around - the smell reminiscent of citronella, a strong hint of its use as an insect repellant by Vanuatuans. Another tree was said to be a cure for stomach ache and so on. The highlight of our tour, a glorious refreshing swim in a lagoon created by the river’s path along the foot of a steep cliff forming the valley wall on the far side of the village. Dicky described the experience as the best fresh water swim he had ever experienced.

On our return and before lunch the chief of the tribe gave a moving speech about the vision for his people. A vision which aspired to Erromangan people having the advantage of the technology available to westerners while retaining the customs and traditions of tribal Vanuatu. It was hard not to be distracted by the chief’s tee shirt, depicting a large cauldron containing a murky bubbling liquid with what looked like one or two human heads bobbing just above the surface, a person with a large wooden spoon stirring its contents and blazoned across the top the words, ‘Cannibal Soup’.

Efate Island, goodbyes and onwards

We sailed to Port Vila, Efate Island, the capital of Vanuatu to find a mooring buoy with attached wooden board bearing Walrus’ name painted in black letters on a white background. Walrus’ arrival was expected and our World ARC yellow shirts team, Lesley and Paul, had thoughtfully reserved one of the buoys closest to the dinghy dock ashore, much to our surprise and delight. We kept our fingers crossed that Walrus’ dinghy could hold up for just a few more days.

Port Vila was more developed than the previous places we’d visited in Vanuatu, with a commercial port alongside our moorings and all-inclusive hotel opposite. The town had been affected by the December 2024 cyclone and, in the main street shops and the vegetable market remained closed. If this paints a somewhat lack lustre image, then the Waterside Restaurant and yachties’ facilities owned and managed by a larger than life Australian Harbour Master full of good cheer, certainly made up for any initial disappointment. Steve ran a tight ship, which was helpful, given our short turnaround and need to prepare for the coming 1115 mile passage to Mackay in Australia. Before we had time to blow up our now rapidly deflating dinghy (renamed by Dicky ‘Inspector Clouseau’s Parrot’ after an apparently hilarious scene in a Peter Sellers movie involving an inflatable parrot - I’ll leave the rest to your imagination or a Google search) our friend the harbour master had Walrus tied up alongside, her port and starboard tanks filled with diesel and water respectively. On that first evening, despite constant pumping to keep the dinghy afloat, water gushed in between the gaping transom (back piece) and dinghy sides, as we travelled the fifty or so metres to shore. Walrus’ crew arrived at the bar soggy and wet. I savoured that evening’s on-arrival margarita, as my dress dripped, and we caught up with our fellow World ARC crew members. What better way to recover from a dinghy ride drenching. If you’re wondering, we managed to get the dinghy and ourselves back to Walrus in one piece, just. For some weeks I had been researching ‘dinghies with soft bottoms’, most have a hard aluminium base to protect from damage when going ashore over sharp rocks or coral. The down side to these dinghies, when deflated they took up a space larger than that available on Walrus’ small foredeck. I had finally settled on a True Kit dinghy made in New Zealand with delivery to Australia infinitely possible, and vowed to place the order the following day.

By the next morning, one glance at Walrus dinghy’s sunken state, her transom trailing below the water, hanging off the now flaccid side chambers, said it all. Walrus dinghy had reached the end of the line. After some negotiation we squeezed into the smallest of gaps on the pontoon, freeing us up to clamber on and off Walrus over her bow. Dinghy No. 1’s demise was sealed as Dicky cut up her pvc chambers into four or five pieces with Walrus’ sharpened bread knife. I deposited the remains, unceremoniously in the rubbish bins behind the restaurant. A sad end to a dinghy which, marketed as a yachting accessory that would ‘Equip for Adventure’, had had more than her own share of adventures. Dinghy No. 1, you may recall, notably defied her destiny when a non-bowline bowline knot led to her disappearance in the Pacific Ocean. Her retrieval two and a half miles out to sea nothing short of a miracle. This escapade led to the non-bowline bowline knot tier receiving an award of a piece of rope with set of instructions at the next World ARC prize-giving event and Walrus’ dinghy gaining a reputation for straying tendencies. Not long afterwards, when a five inch gash in one chamber again threatened to end Dinghy No. 1’s useful days and her place on Walrus foredeck, Gerald’s patience and some strong glue revived her for a further stay of execution and numerous fun and definitely damp journeys to and from shore. Finally Walrus and her dinghy had parted company and we were dinghy-less, at least for the time being.

Our last few days in Vanuatu were spent getting to know a little more about Efate on a Warld ARC organised tour, provisioning for the next eight day passage, and spending time with skippers and crew of the remaining thirty or so yachts reminiscing over the ups and downs of the nautical miles covered so far, before saying goodbye to the boats that were leaving the World ARC Rally to take a different route, either home or other shores.

On the way back from a trip to swim in a freshwater lagoon at the base of a spectacular waterfall nestled in lush rainforest Roy, our driver explained the meaning behind the design of the Vanuatuan flag. Red represented the sovereignty of the Chiefs; green the lush green rainforest of the countryside, a yellow Y reflected the shape that Captain James Cook ascribed to the Vanuatu archipelago when he visited in 1775-9. In the centre a circle formed from two wild boar tusks reflected the continuing practice of barter and the significant role of pigs in the economy. David our wonderful guide on Erromango had already introduced us to the practicalities of maintaining with tradition and the place that pigs play in Vanuatuan life. It was the custom for fathers to pay the dowry of one pig on the marriage of a daughter. David had four daughters and showed us evidence of his preparation for at least one daughter’s wedding - the pig was firmly penned not far from the yacht club, awaiting its’ inevitable fate.

After visiting islands with basic local vegetables and fruit for sale or barter it was a relief to find that Efate’s more developed economy meant access to a supermarket, albeit a fifteen minute walk away. We were excited to find fresh bakery and meat and fish counters in store. Ted and I trailed the aisles, adding treats such as chocolate, beer and ginger beer, even some crisps, a Dicky favourite, that had long since disappeared from Walrus’ lockers. Two shopping trolleys later and we were in need of a taxi. Suffice to say we made it back to Walrus after a number of attempts to secure a cab had failed and two local women took pity on Ted and asked the taxi driver from which they’d just alighted to take us back to the marina.

Nearly time to set off again on the final leg of the first half of the World ARC Rally 2025-26. A prize giving celebration, partying and goodbye to two boats’ whose crew we’d come to know and love. We were indebted to Chillalot for Kevin’s knowledge and reassuring advice about all things mechanical and his generous loan of tools, I would miss Geerte’s jewellery-purchase advice and their boys, Gus and Joep had become a much loved part of the World ARC family. Entre Nous boat owners, Peter and Deborah had been generous hosts we would miss their company and tales of cruising the world. We also said goodbye to Richard (chief beach BBQ organiser) and Paula in Vanuatu, The shared experience of circumnavigation by yacht had been bonding, which perhaps was inevitable given the intensity and out-of-the-ordinary nature of the experience. The World ARC had fostered a strong sense of community amongst yachts and their crew and I’m sure I’m not alone in feeling a genuine sense of loss as boats and familiar faces peeled away from the group. Onwards and upwards as an ex-colleague used to say.